The Barabar Caves - 7: The caves at Nagarjuna Hill

The road to Nagarjuna Hill got bumpier and bumpier - at times I thought that the Ambassador motor car could not cope with such punishment, and that it would be better if we walk. The driver, though, was quite confident in his abilities and those of the car so we continued on, driving slowly over the large rocks that defied the name of 'road' in any more normal circumstances.

There are three caves situated on and around Nagarjuna Hill: the Vadathi-ka-Kubha, the Vapiya-ka-Kubha, and the Gopi-ka-Kubha. I was very pleased to have the chance to visit all three of them on this visit, and I hoped that they would provide new clues to the story of 'A Passage To India' that Forster tells.

Driving into the valley at the base of Nagarjuna Hill, I was amazed to see the large piles of boulders, stacked every which way. They reminded me of some giant infant, tossing his bulding blocks in anger. One pile, shown in the photograph below, had a single circular boulder balanced on the top of others. How had it got there? Was it, perhaps, the 'Kawa Dol' that Foster had mentioned: the rocking stone that contains a 'bubble-shaped cave that has neither ceiling nor floor, and mirrors its own darkness in every direction infinitely. I was to find out more about the Kawa Dol a little later that day.

We parked the car in the rough grassland and paddy that covers much of surrounding area, then proceeded along a newly-made cement path towards the first of the caves, the Vadathi-ka-Kubha.

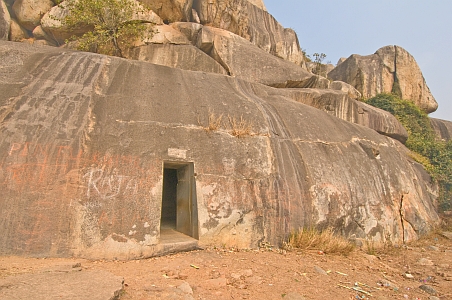

The cave entrance is easy to miss, situated in a cleft between two huge boulders, though now a line of stones marks the way towards it from the path.

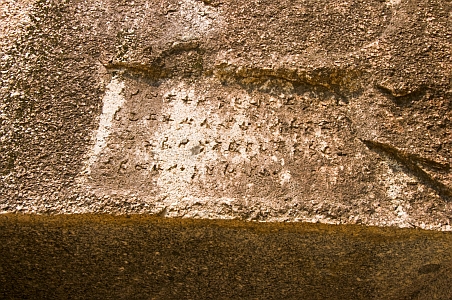

A meticulously cut rectangular entrance doorway to the cave opens from the end wall of the huge boulder. Above the doorway is a roughly smoothed rectangular panel, with four lines of ancient writing carved upon it.

Passing through the doorway, I entered the passageway that leads to the cave interior. The rough surface of the exterior boulder changes almost magically in the passage, as the walls, floor, and ceiling have been chiseled to an astonishing degree of smoothness that would be difficult to acheive even with today's tools and techniques. That it was done more than 2,200 years ago is truly remarkable.

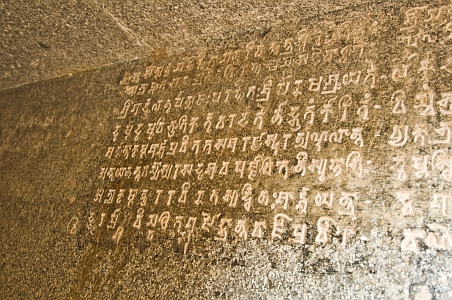

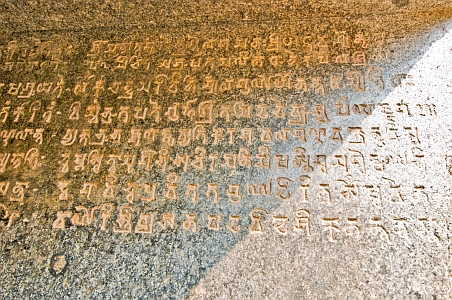

On the upper right wall of the passage, just next to the entrance doorway, can be seen more carved text, using what appears to be a different character set from than that used outside. There are eight lines in total.

At the far end of the passageway, just as it enters the cave interior, are four circular sockets cut into the rock. These were used to mount a pair of doors, probably constructed from wood, that would originally have closed the entrance to the cave interior.

Once again, the available light in the interior was minimal, and a huge contrast to the light coming from the passage, so in order to get a balanced photograph of the scene, it was necessary to use High Dynamic Range photography techniques. Each of these photographs, above and below this paragraph, are compositions of 5 separate images, each taken with 1 f-stop of bracketing between the images. The end result is a clear and balanced image, similar to that which the human eye and brain really sees, but impossible to represent using a single photograph.

As can be seen, the Vadathika Cave has a circular vaulted chamber, with no defining line between walls and ceiling. The entrance wall through which the passageway passes is flat. The opposite rear wall, however, is curved. The finish of walls, ceiling and floor can be correctly described as glasslike. It has been carved, smoothed, and then polished to an astonishing degree of finish, which has remained intact for over 2,000 years.

The Vadathika and Vapiyaka Caves are situated next to each other, in adjacent but separate boulders. The photograph above shows the path to the entrance of the Vadathika cave crossing the centre of the image, going to the left. The entrance to the Vapiyaka cave can be clearly seen to the right.

The name of the cave: 'Vapiyaka' translates as 'Cave of the Well', and many web references claim to have seen a dried-up well in front of it, though I didn't notice any evidence of this myself. The Vapiyaka cave has a very impressive facade. The front of the boulder that contains the cave and through which its entrance was carved is sloping, and so a small portico or entrance has been created, enabling the entrance doorway itself to remain vertical.

As in the Vadathika cave, the passageway and interior of the Vapiyaka cave has the same glasslike finish on the rock surface. Unlike the Vadathika cave, the Vapiyaka cave passageway has no inscriptions carved upon it. The interior of the Vapiyaka cave is different too. Rather than a smoothly circular vault with no defining line between walls and ceiling, here the walls and ceiling are divided by a distinct line, the walls are vertical, and the interior outline is that of a truncated barrel. The rear wall of the Vapiyaka Cave is also flat, not curved.

There was now just one more cave in the Nagarjuna group still to visit: the Gopi-ka or Milkmaid's Cave. The Gopika is the biggest of the three. Inscriptions found within and above the doorway refer to its excavation in 214 BC when King Dasratha, the grandson of Asoka, ascended the throne and bestowed the Nagarjuna caves to the Ajivikas.

Unless there is someone to show you, the path to the Gopika cave is not immediately clear. The photograph above shows the approach to the cave. Its route is a little more obvious these days, due to the v-shaped approach path that can be spotted in the picture, centre-left. This path contains the steps. Once you arrive at the base of the steps, the way is clear for all to see.

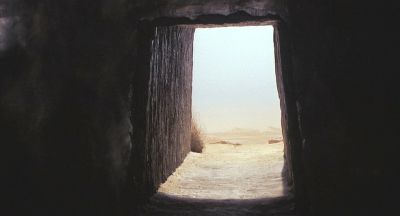

The moment I saw the Gopika cave I realised where David Lean had got his ideas from for the Marabar Caves portrayed in the film. Both the layout and the approach to the upper Marabar caves used in the film-set mirror the layout of the Gopika cave here at Barabar. I do not know whether the current approach steps were made when Lean or his location-scouts surveyed the area, but the difficult ascent and the subsequent doorway must have been the major factor that decided the final look of the caves near Banglore.

The interior of the Gopika cave is impressive. The biggest of the three in the Nagarjuna group, it measures (according to 'Middle Land, Middle Way By S. Dhammika') 12.3m long, 5.2m wide, and 6.5m high. Stupidly, I had omitted to bring a tape or other measuring device with me on this visit, so cannot verify these figures. Both end walls of the Gopika cave are semi-circular, the roof is curved, and the walls are vertical.

I have included above a screenshot from the film that shows the studio set that Lean created to show the view out from his Marabar cave. In the two photographs below, you can see the actual views down the passageway of the Gopika cave, looking out over the Bihar countryside. The similarity to the actual views at Barabar will be obvious to all.

Carved on the wall of the Gopika cave passageway are 10 rows of text. I do not currently have a translation for it, but if one turns up it will be included here.

There are four lines of engraved text on a roughly smoothed panel above the doorway of the Gopika cave, but I do not have a close-up image of this. From other research, I believe this text to be in the Pali language.

The Gopika cave was the last cave I was to see that day, but I still had a little more sightseeing to come. Whilst talking to the caretaker, I had mentioned the Kawa Dol referred to by Forster. Imagine my surprise when the caretaker told us that he not only knew about it, but informed us that it was quite near to the Barabar caves, and could be visited quite easily. We boarded the Ambassador motor car once more, and headed in the direction he indicated...

Please visit Page 8 of the Barabar Cave series..