The Barabar Caves - 2

Since writing and publishing the previous page on the Barabar Caves, I have had numerous requests for further information, and for permission to use the photographs in books and on other websites. I was a little embarassed with the quality of some of those images, and felt that I could do better, so in 2009, I made a return visit to the Barabar Caves to see how things had changed. Equipped with a good digital camera: the Nikon D300, and a suitable tripod and lenses, I was determined to capture a better series of photographs that correctly documented the caves and their surroundings.

Arriving at Gaya railway station on a day at the end of January, I booked once more into the Hotel Ajatsatru, which had added some new rooms in an extension since my last visit. Paying a visit to the Tourist Information Office at Gaya railway station, I was pleased to meet the same gentleman as before, still working there. I explained that I wished to re-visit the Barabar Caves, and he tried to dissuade me from making the journey, saying that it was too dangerous to visit these days, and that I should not think of returning. Having come all this way, though, I was not going to let a little thing like armed bandits put me off from seeing the caves again, and having convinced him of my determination, he eventually located a driver who was prepared to take me, and a suitable price for the trip was agreed. This time, though, the head of the Tourist Office didn't insist on accompanying me on the journey as well!

Promptly at 8 am the following morning, my driver was waiting outside the hotel. I think it best not to record his name here, due to possible bandit reprisals, so I shall refer to him as Mr Patel. The vehicle this time was an Ambassador motor car, a pleasant change from the auto rickshaw of last time, and much more suitable for such a long journey. Though no longer the exclusive car of India, it is still a common sight throughout the country, and well adapted to the rough roads found in Bihar. Its reliability would be severely tested later on in the day! We set off straight away, driving through the poorer area of town then heading north on the main road that leads to Jahanabad, and from there to the state capital, Patna. After 30 minutes or so, we arrived at the small town of Bela, and ignoring my own recommendation to enquire about the current state of safety in the region at Belagunj Police Station in case they too tried to persuade me not to continue my journey, we turned east along the bumpy track that leads to the caves.

To say that the track from Bela to the Barabar Caves is bumpy in an extreme under-statement! Though surfaced with tarmacadam at one period in its history, possibly before the British quit India, it has received little if any maintenance since then. What tarmacadam remains is severely fractured and pot-holed. Its absence is to be preferred, as the dusty track beneath is a little smoother to drive. The traveller is given many chances to assess this comparison, as the surface appears and disappears with great regularity. Mr Patel slowed the Ambassador to a crawl, and in this manner we progressed through arid farmland, interspersed with small farm houses and shacks. We met occasional vehicles: a tractor or two, a few auto rickshaws, and even a battered old country bus. Bad though the road is, people live here, and all have to get to and from town for the market and other requirements.

After a seemingly endless journey, in fact just 9Km, we left this road and headed north along an even worse track that seemed to be composed of a gravelly surface on which had been embedded a quantity of sharpened rocks, the size of large grapefruit. Mr Patel inched the Ambassador along this until we arrived at a number of buildings that marked the entrance to the area where the Barabar Caves are situated.

Much had changed from my last visit, some 16 years earlier. Then, the caves had been all by themselves, lonely and isolated within the rocky valley, but now, some effort had been made to enhance what must be one of the few tourist attractions north of Bodh Gaya. A broad concrete path had been added, a parking area, and a house for the holy man who used to be the sole inhabitant of the site. A new well had been dug, and a pumphouse had been added. Extra buildings provided accomodation for the holy man's acolytes. The holy man himself, the same one as before though now much aged in appearance, now had a small temple near the well in which he could conduct darshan, though was, no doubt, still quite capable of climbing the adjacent Siddheshwar Peak when required to.

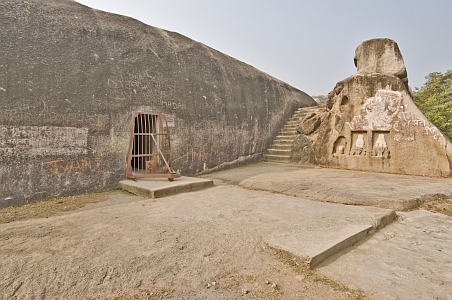

I followed the path to the caves. What had once proved quite difficult to locate in the boulder-strewn valley was now easy to follow, thanks to the new path. But all was not well. Arriving at the first of the caves, the Karan Chopar cave, I saw an ugly steel gate had been fitted to the cave entrance, and securely bolted into a new concrete pad beneath. A large and rusty padlock stopped any chance of moving it and thus gaining entry within. Was my expedition to view and photograph the cave interiors to be thwarted after all?

I could do little beyond poking my camera through the bars of the gate and attempting to capture a view of the smooth entrance passage. It was most disappointing. Why had this been done? A clue might be provided by viewing the numerous examples of grafiti on the rock face outside. Adding to the facilities of the Barabar Caves had increased the number of visitors, and with visitors invariably comes litter and grafiti. The Archeological Survey of India, in an effort to protect this vital site of antiquity, had felt it necessary to limit access to the cave interiors.

Please visit Page 3 of the Barabar Cave series..